Photos of Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi

Photo Courtesy of Argonne National Laboratory

Atomic Energy Tablet Dedication (1947)

University of Chicago Photographic Archive, [apf3-00224], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Research Institutes Ribbon Cutting Ceremony (1950)

University of Chicago Photographic Archive, [apf2-06417], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

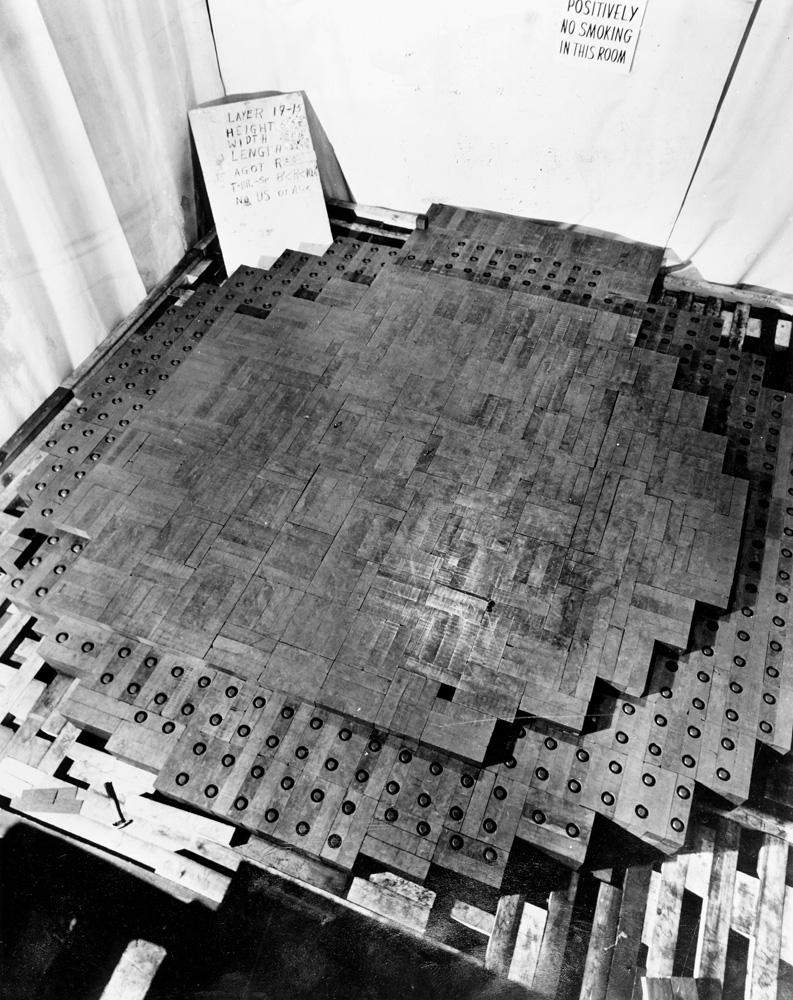

Atomic Pile, Construction of 1st Nuclear Reactor (1942)

University of Chicago Photographic Archive, [apf2-00502], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

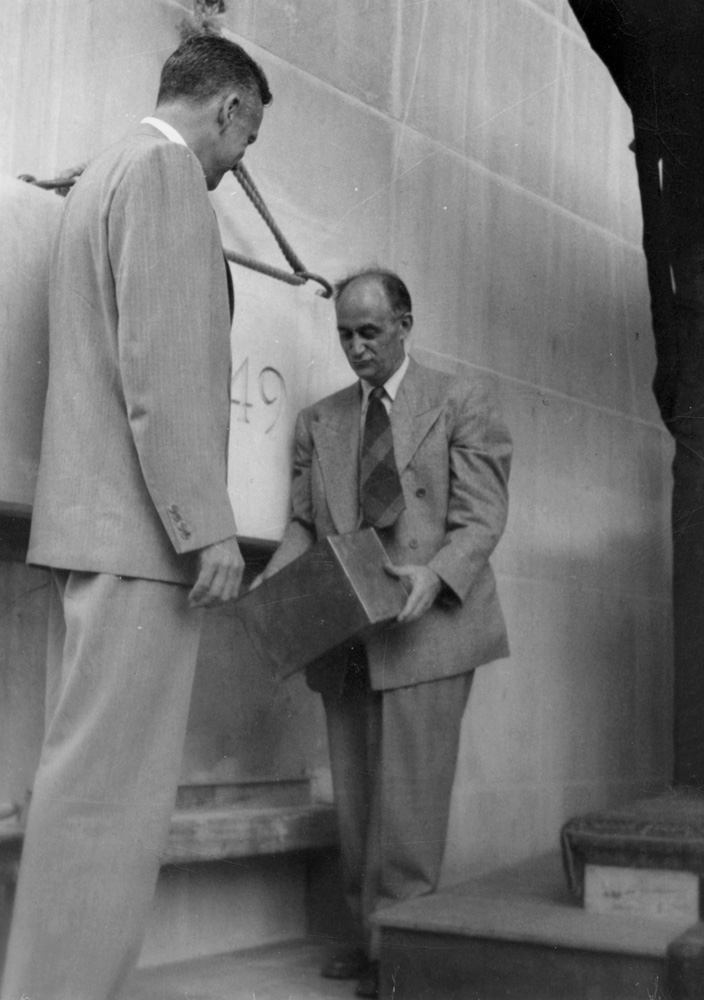

Dr. Fermi holding time capsule with Dr. Hutchins

University of Chicago Photographic Archive, [apf2-06369], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

The Nobel Prize

- 1938 Nobel Prize CertificateEnrico Fermi's 1938 Nobel Prize certificate, from the University of Chicago Library's Enrico Fermi Collection

Biographical Note

(From the Biographical Note, Guide to the Enrico Fermi Collection, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

Enrico Fermi (1901-1954), Charles H. Swift Distinguished Service Professor of Physics at the University of Chicago, and 1938 Nobel Prize winner in physics, is best known to the general public for his leadership of the Manhattan Project team, which succeeded in obtaining the first controlled self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. This experiment, which was carried out at the University of Chicago on December 2, 1942, made possible the development of the atomic bomb. Fermi was also among those who developed the bomb, at Los Alamos, New Mexico, to operational level. Even after his acceptance of a professorship of physics at the University of Chicago at the close of the war, he continued to work in an advisory capacity for the Atomic Energy Commission, the Office of Naval Research, and related bodies.

Fermi was born in Rome, Italy, on September 29, 1901, the third child of Alberto and Ida (de Gattis) Fermi. Alberto was employed by the Italian railroads as an administrator; Ida had been a school teacher prior to her marriage. While still a teenager, Fermi developed a strong interest in mathematics, which, under the guidance of Adolfo Amidei, an engineer colleague of Alberto's, developed into an interest in physics too. Also during his adolescence, Fermi, along with his close friend and future physicist Enrico Persico, spent many of his days designing and conducting scientific experiments, including one to determine the precise density of Rome's drinking water. According to Amidei and to the evidence of an early research notebook in this collection, Fermi was a prodigy as a theoretical physicist. In November 1918, just after he turned seventeen, Fermi began his higher education at the Scuola Normale Superiore at Pisa on a scholarship. Less than four years later he received the degree of Doctor of Physics, magna cum laude, from the University of Pisa, based on experimental work that he had conducted on X-rays.

Following his studies in Pisa, Fermi used a fellowship from the Italian Ministry of Public Instruction to study at Göttingen, a university then at the height of its fame in physics. He worked there with Professor Max Born and was a fellow student of Werner Heisenberg, who was to make some of his most important contributions to the field of theoretical physics within the next two years. During the subsequent academic year, Fermi taught at the University of Rome and then, in 1924, at Leyden in Holland, where he worked with Professor Ehrenfest and his pupils, who included Sam Goudsmit. During the next two academic years, Fermi held an appointment at the University of Florence, where he began work on what would later come to be known as the "Fermi-Dirac statistics." The Fermi-Dirac statistics enabled not only a deeper understanding of the conduction of electricity in metals, but also the development of a widely used statistical atom model.

Fermi was appointed Professor of Physics at the University of Rome in 1926, where he lectured until 1938. From 1926 to 1932, he joined other European physicists in working primarily on the theory of atomic structure, which Fermi helped to complete in the form that it is known today. By 1932 his attention shifted to the growing fields of theoretical and experimental nuclear physics. Soon thereafter, he developed his theory of b-ray emission, in which he gave mathematical evidence for the existence of the neutrino. This proved to be one of his major achievements in physics. Working with several collaborators at the University of Rome, including Edoardo Amaldi and Bruno Pontecorvo, Fermi then went on to study the slowing down of the neutron, another recently discovered atomic particle, in hydrogenous materials. By capturing the slow neutron in atomic nuclei, he made a comprehensive study of a big class of artificially radioactive substances. His work on neutron physics was recognized in 1938 when he received the Nobel Prize for Physics. The techniques and theories that he worked out during this period were also those that he later used in the "exponential pile" experiments which led to the development of the first controlled uranium-graphite reactor.

During this remarkably productive period scientifically, Fermi was finding the political situation in Italy increasingly intolerable. In 1928 he had married Laura Capon, the daughter of a respected Jewish family in Rome. While Fermi, like many of his colleagues in this period, was a member of the Fascist Party for reasons of professional necessity, Italy's enactment of anti-Semitic racial laws in 1938 caused him to consider emigration as a protection for his family. That family now included two children, Nella and Giulio. Recognizing the occasion of his family's travel to Stockholm for the Nobel awards ceremony in 1938 as an opportunity for escape, Fermi and his family departed for the United States from the ceremony. Shortly thereafter he was appointed to a professorship of physics at Columbia University.

Soon after his arrival in the United States, Fermi became instrumental in sparking the U. S. government's interest in developing atomic energy for military purposes. Working with other physicists at the Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago, which had been established for precisely this reason, he led a team to design and construct an exponential pile (sometimes referred to as Chicago Pile 1) in an empty room (formerly a squash court) under one of the university's athletics fields. The first-ever controlled self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction took place in that pile on Decmber 2, 1942. During the subsequent two years, Fermi conducted various experiments using the reactor, as well as assisted in the development of a larger reactor at the nearby Argonne Laboratory. On July 11, 1944, Enrico and Laura Fermi were naturalized as citizens of the United States.

Following a brief period during which he worked primarily with the DuPont Company developing plutonium on an industrial scale, Fermi moved his family in August 1944 to Los Alamos, New Mexico, where the War Department's top-secret Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb was already well underway. As Associate Director of the project, he oversaw all experimental physics projects already in progress, conducted a few experiments on neutron cross section measurements, and observed the first test of the bomb at Alamogordo, New Mexico. Fermi then served as one of four scientific consultants to President Truman's advisory Interim Committee, which, after lengthy deliberation, recommended that the bomb be used for military purposes. Fermi received many citations and awards for his contributions to the war effort, including the Congressional Medal for Merit in 1946.

Resuming his academic work in 1946 at the University of Chicago as the Charles H. Swift Distinguished Professor of Physics, Fermi became a member of the newly formed Institute for Nuclear Studies at the university (the present Enrico Fermi Institute for Nuclear Studies). During the subsequent eight years of professional activity, he assisted in the development of Chicago's 450 Mev synchrocyclotron and of several electronic calculating machines. He worked in an advisory capacity to the Atomic Energy Commission and its associated laboratories, served as the President of the American Physical Society in the early 1950s, delivered many lectures, taught several university courses, and published numerous papers on various theoretical and experimental topics in physics. These papers included studies of neutron diffraction by crystals, of analogies between the properties of neutrons and optical waves, of the physics of mesons, of the origin of cosmic rays, and, in the last year of his life, of the polarization of proton beams on scattering.

Fermi spent the summer of 1954 in France, Germany, and Italy where he toured, delivered lectures, and reunited with various European friends, relatives, and colleagues. He was already in the final stages of an incurable cancer. Returning to Chicago in September 1954, he spent the last two months of his life visiting with friends and family and undergoing various medical procedures. Just days before he died, the Atomic Energy Commission created a special award for Fermi in recognition of his distinguished service to the nation as a scientist.

Enrico Fermi died in his sleep at his Chicago home on November 29, 1954.

Contact Information

Andrea Twiss-Brooks

Director, Humanities and Area Studies

Chemistry and Geophysical Sciences Librarian

Send Email